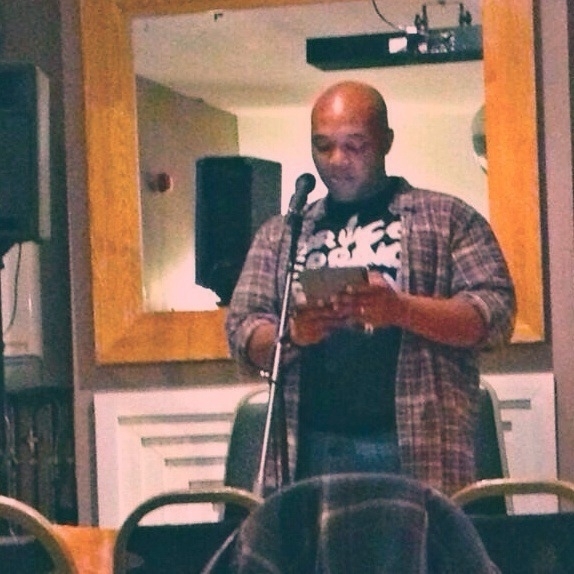

we are with the poet,

seeing, hearing, and feeling

the same things at the same time,

a shared but fleeting residence in the house of sensation and image.

It’s as if we’ve stumbled upon a hidden chamber in a well-known building, entering a room where the atmosphere is thick with the texture of memory, the aroma of distant lands, and the murmur of bygone conversations.

A river flows past us, and we see it not just as a body of water, but as a time-traveling storyteller. Each ripple a story, each wave a generation, each stone a historical marker polished by the relentless touch of the present brushing up against the past.

Isn’t that how the great poets, like Rumi or Emily Dickinson, infuse the natural world with layers of meaning?

A bird is never just a bird; it’s an emblem of freedom, a song of solitude, a messenger between realms. A tree isn’t merely a fixture of the landscape but a sage that has observed the secrets of earth and sky, holding in its rings a coded autobiography of nature’s whims and the world’s heavy sighs.

And it’s not just sight;

it’s a symphony of the senses.

The jarring collision of clattering pots in a busy kitchen is reimagined as a percussion section in the soundtrack of domesticity. The aroma of freshly ground coffee enveloping the early morning not only wakes you up but calls forth other awakenings—of dreams, of ambitions, of unspoken love perhaps. What you hear is more than just sound waves; it’s the harmony—or dissonance—of life’s myriad complexities.

These poets allow us

to hear the hidden chorus

in a lover’s whisper or

the secret plea in a baby’s cry.

But, oh, to feel.

That’s where the real magic lies, isn’t it?

When reading Pablo Neruda or Sylvia Plath, one doesn’t just skim the words; one touches the very fabric of their emotions. It’s an empathy, immediate and raw, as if their verses were inked not in pigment but in the very plasma of the human experience.

Neruda’s odes are so filled with texture, you might feel the rough skin of an artichoke or the silkiness of wine as it slips through the goblet of your mind. Plath’s confessions don’t merely expose her feelings; they lay bare your own, unveiling the shadowy realms you dare not visit.

The poet’s canvas is expansive, stretching across geographies of the heart and topographies of the mind. They are both mapmaker and tour guide, drafting coordinates that may begin in the flesh but resonate in the spirit. Standing beside them, we are more than passive observers; we are fellow wanderers, seekers on a common but infinitely varied quest for truth and beauty.

And as we pause, catching our breath in a momentary stillness, we confront an unsettling revelation. Are we, through this act of reading, merely catching a reflected glimpse of the poet’s world—or are we, perhaps unknowingly, also the poets of our own lives, continuously writing, erasing, and rewriting the manuscript of our existence?

If your life were a poem,

what would be its central metaphor?